Sienna Jackson/Special to The Bull

The ‘Arab Spring’ is the coined term for the 2010-11 wave of political unrest throughout the Middle East. From Tunisia to Egypt, Bahrain and Yemen, the citizens of Arab and Islamic nations throughout the region have risen against their governments.

This widespread demand for democratic rule across the Middle East could mark a turning point for a region fraught with political turmoil, violence and war; a region that has been a critical strategic interest on the world stage for thousands of years.

Governments in the Middle East are notorious for corruption, whether they are authoritarian regimes of dictators or thin facsimiles of democracy, mere masks for puppet administrations under the thumb of foreign powers.

Neither form of government is satisfactory, and neither serve the interests of their constituent peoples, many of whom are deprived even the most basic of human rights.

And besides the abuses of government that have become such a norm, there is also the issue of fundamentalism to consider. People, some educated, some poor, all angry, have resorted to jihad and militancy in an attempt to seize power for themselves.

Driven by anger and, perhaps, a sense of impotency and helplessness, people are using violence and fear mongering as the measure of first resort.

Extremism in the Middle East has complicated and impacted every facet of foreign policy, because even in the end, a corrupt government is preferable over terrorism, at least in the minds of the West.

Still, for the majority of people living in the Middle East, terrorized by government and fundamentalists alike, there is little hope of empowerment – true empowerment, and not the vision of power through violence.

That is what makes the Arab Spring so remarkable. For the first time in recent memory, the people of the Middle East – the young, the middle class, the idealistic – are marching in the streets, speaking truth to power regardless of their government’s attempts to silence and subdue.

Putting aside the IED for incriminating viral videos, the propaganda tape for the live blog is what makes the Arab Spring so hopeful.

This movement has already sent shockwaves throughout the rest of the way, not only for its characteristic nonviolence, but for the fact that it’s working.

The protests in Egypt rode in on the fervent energy of the Tunisian protests at the end of 2010, targeting Egyptian president Mubarak and his secret police, the abuses of government and the censorship of the people.

Egypt’s revolution was extensively covered by the international press, Al Jazeera played an important role from a media standpoint with their intensive coverage, and the Internet played a starring role as the link between fellow protesters and an information vehicle to the world.

What made the resistance movement in Egypt against President Hosni Mubarak so captivating to the rest of the world was the demographic of the movement itself – young, educated and technically savvy middle-class youth and women – as well as the ingenuity of the protesters.

When the Egypt government flipped the “Internet kill switch” that barred Egyptians from most Internet and phone services, the people got creative, organizing in IRC chatrooms and sending fax-to-Internet messages in code to revolutionaries and press alike.

Despite the Mubarak regime’s attempts to suppress rebellion, the government was eventually no match against the persistence of the youth of Egypt – and, like the Tunisian president before him, Mubarak also resigned.

Now in the months following the ousting of Mubarak, women struggle to maintain the strong role that they played in the revolution, which has turned to the business of rebuilding the country.

While the protests were secular philosophy, the Muslim Brotherhood (one of the oldest and most influential Islamic movements in the world) has begun to take root in post-Mubarak Egypt.

The Brotherhood is banned from political activity in Egypt, under a law constituted by Mubarak that restricts organizations with religious backgrounds and intent from forming political parties – a law Mubarak passed after the Brotherhood’s party, Ikhwan, won 20% of the seats in the Egyptian legislation in 2005.

This constitutional repression of all opposition movements is partly what fueled the public ire against Mubarak, but it was only until the revolution drew to a close that the Brotherhood resurfaced in the Egypt political landscape and offered public support to the rebels.

This resurfacing has drawn concern from the West over the possible future power of an organization whose most popular slogan is “Islam is the solution.”

The Arab Spring thus far had been nonviolent on the side of the protesters themselves, something uncharacteristic of most political uprisings in that part of the world.

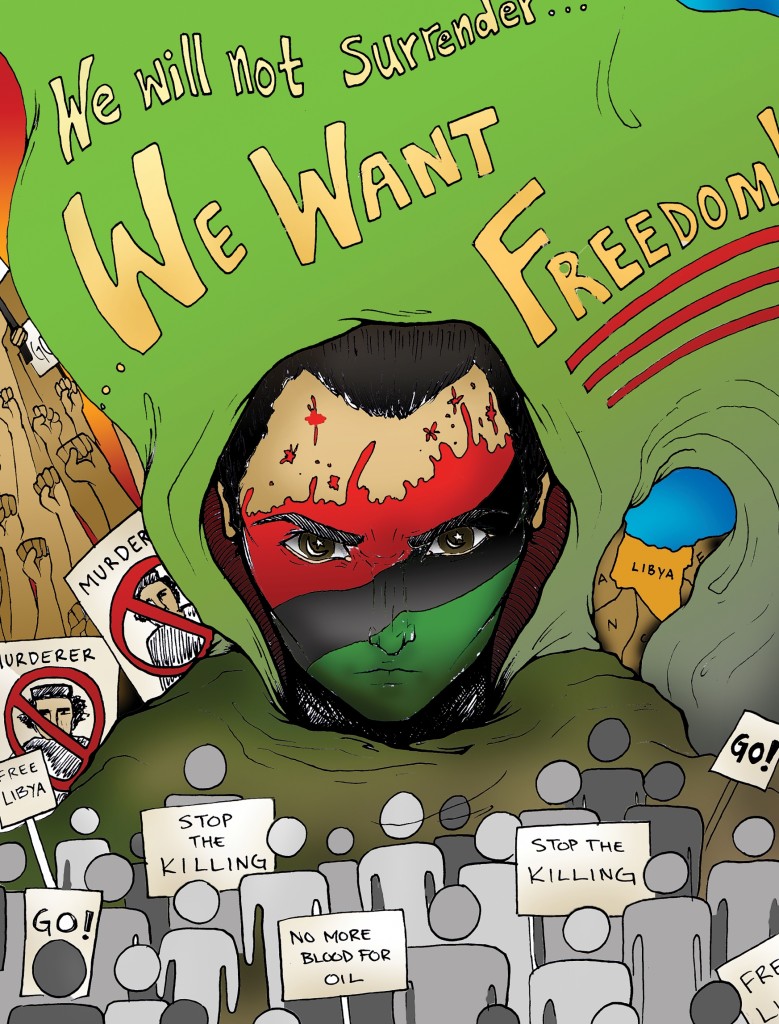

But in the oil-rich nation of Libya and, as of March 25, the republic of Syria, violence has sparked on both sides of the conflict between government oppression and public resistance.

Libya’s current leader, Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, has asserted his intention to wage an extended war against the rebels.

Libyan military and Qaddafi’s remaining supporters are currently laying siege to rebel controlled-towns whilst Qaddafi remains sequestered in Tripoli, surrounded on all sides by rebels armed with AK-47s and a violent disgust with his regime’s violent response to what had initially been peaceful protests.

The United States (regardless of its economic woes or China’s rising star) still enjoys great influence on the world stage, as the major contributor of both money and firepower in the U.N. Security Council.

Qaddafi’s violent response to protesters has sparked international outrage and, for the first time, the United States is taking a military stance in a Middle Eastern nation with full backing from the international community.

This support likely bolstered President Obama’s own resolve to act on behalf of the Libyan resistance movement against Qaddafi, establishing a no fly zone over the country in cooperation with a largely French-led coalition.

But President Obama has toed many a delicate line in dealing with the Arab Spring and all of its consequences for the world at large. The removed but supportive stance that the U.S. took in regards to the protests in Egypt, Tunisia and Bahrain were appropriate and non-military.

Currently, the combined military actions of the U.S. and allies in the Libya is being turned over to the hands of NATO, and the United States is not taking a clear leadership role in the effort.

And in now Syria, with Syrian troops firing on civilians in several cities, it is unclear just how proactive a role the U.S. will now play in an increasingly bloody spring.

Whatever the president chooses next, it cannot be toward an occupation – not when the U.S. is currently entrenched in two separate Middle Eastern countries.

The U.S. and its allies must be retrospective and forward thinking in this now-NATO led effort in the region: they must have a clearly defined goal in mind, a point of withdrawal, and the understanding that no nation has ever benefited from prolonged occupation, most especially not in the Middle East.

The world finds itself at a crucial juncture in history, with several Middle Eastern countries embroiled in civil conflict on an incredible and interwoven scale.

Whatever the outcome may be, this moment, this turning point, belongs to the people of the Middle East, the young and idealistic and brave. In retrospect, we can say that much.