Rapper and Producer on their plans to take over an industry

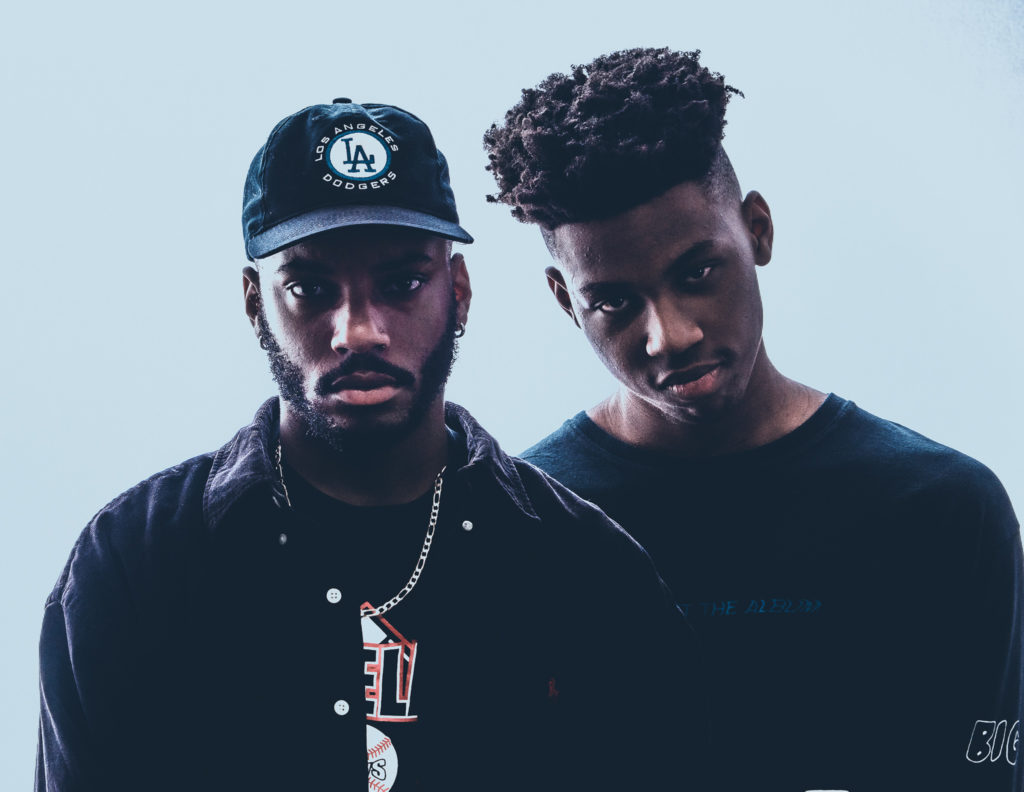

Ryan “Hundo” Williams and Justin “JustBeatz” Garner pose in the photo studio at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, Calif., on Oct. 16, 2019.

At 18, during one of Ryan Williams’ shifts at Footlocker, a colleague grew sick of listening to his fantasies of being a famous rapper. He took him aside and said, “If you want to be a rapper so bad, prove it.”

Williams went home that night and recorded his first song. Anxiously, he put it on Facebook, the pseudo streaming service of music for teenagers in 2011.

After receiving some praise—not only from his friends at work, but also from random people online—he realized this actually could be his career path.

“It wasn’t a definitive thing where I was gloating, like I’m the man at this. That didn’t come until later,” Williams said. “I only feel that way now. But then it was like, I’m actually pretty decent at this, like if I really worked at it, I could turn this into something,”

Years later, after falling in and out of love with the rap game, Williams began to take the art form seriously. Now 27, he is recognized by thousands as Hundo, the up-and-coming San Fernando Valley rapper with a promising career as a signed, featured artist for Sprite, the soda under the Coca-Cola Company.

Williams believes being a rapper today is more attractive than ever, but that many don’t see the power the form has when used as a proactive voice for change.

“Maybe being a musician appears cooler than other jobs, but the core of what I do is still to support the community, to speak up on important issues, to find a way to get involved and make a change, whether it be on the smallest scale or the largest one,” he said. “It’s evident in the music I put out. It’s evident in the rapping.”

Williams spent many years deciding on what he calls “his purpose.” He worked a couple of blue-collar jobs while he studied to be a youth pastor.

“I could have sworn that I was going to focus on ministry,” Williams explained. “I ended up dropping out of college to pursue ministry and then I left ministry soon after.”

But it was a conversation with God that convinced him to change his direction.

“It was as if God himself spoke to me and was like, ‘If this took you a year to learn how to get better, without any success, would you be OK with that?’ Williams explained. “Once I answered that within myself, and I said ‘yes,’ I knew it was time to take it seriously.”

Williams credits his success from consistent influence on Instagram and other social media platforms, as well as his support group Potluck—an artist collective he co-founded.

“I wanted to create something where it’s not just about the person at the top,” he said. “Those types of organizations, they fail. So I wanted something where it’s like, if everybody cooks, everybody should eat. It’s like, let’s get people to collectively give their talents and we all reap the benefits.”

Justin Garner, who goes by his stage name JustBeatz, is a music student at Pierce College and is Williams’ producer. Garner’s work can be heard on Williams’ latest project This Is Not the Album, which debuted earlier this year.

“To me, it’s the craft,” Garner said. “Performing is cool, but just being in the studio, crafting new music, is always a fun experience. Always.”

When Williams performs live, he raps, Garner provides beats and Erik de Guzman organizes the songs and translates them for a live setting.

“When you get a great performance, it’s just like an intoxicating feeling, like you’ve done amazing and the crowd loves it. But I still love crafting a song,” Guzman said. “The process of putting sound after sound together like pieces in a puzzle, and then it all comes together beautifully. Nothing beats that.”

Garner believes that Williams having a live band gives him an advantage over other rap artists.

“Not to shame anyone who’s rapping over an MP3 for a live performance, but it gets boring,” Garner said. “I think people think its eye candy to see a rapper with a live band. There’s no color with an MP3. It brings color when we step into a room together.”

Samuel Grodin is an adjunct performance professor at Pierce College. He said that having a live band is usually a more preferable option, regardless of the music style.

“It depends on your musical vision, but there is something special about performing in a group,” Grodin said. “You react off of one another, and these reactions can make something great. Rock Concerts, for example, with all the singing and yelling, can sometimes feel like listening to the music aspect of the show becomes secondary to the performance as a whole.”

Many of Williams’ songs cover social topics such as racism, political corruption and domestic violence. But his roots are focused on his backyard.

“If I could change the way that things are around here in the Valley, if I could bring in more jobs, more work into this community, then that’d be cool,” Williams said.

Williams dreams of building his rap career to a global scale, but he also hopes to represent the San Fernando Valley like never before by building a rap culture separate from the Los Angeles scene.

“When I say I’m the best rapper in the Valley, I don’t say that to be mean to other people,” he explained. “I’m bringing awareness to the Valley, and I’m also trying to raise the level of the competition. I want people to really come to this and take it seriously.”

According to an article by The Atlantic, the likelihood of becoming famous as a rapper is 0.0086%, while more than half of people in the United States ages 18-25 wish they were famous for rapping. But Williams isn’t afraid of pursuing his dreams, regardless of the statistics.

“There’s a lot of artists I’ve met that are more naturally talented, but they don’t apply themselves,” he said. “To me, that’s the difference, where I feel like I have an edge.”